Watercolor by Val Littlewood http://pencilandleaf.blogspot.com

Honeybees may be cute, popular and extra fuzzy, but the real proboscis behind most of our region’s fruit crops is a completely different arthropod: the blue orchard mason bee (Osmia lignaria).

Why Choose Mason Bees?

Native to North America, mason bees get their common name from their habit of patching up naturally occurring holes with mud to make nests. While they are similar in size to honeybees (of European descent), the mason bee’s iridescent blue-black color makes it easy to distinguish from its relative, as does its preference to carry pollen on its abdomen versus the honeybee’s choice to transport the goods on its hind legs.

While fruit growers won’t turn down a pollinator, many orchards choose to manage colonies of mason bees instead of honeybees due to their resilience and productivity. Mason bees will keep working hard through moderate rain and temperatures as low at 50 degrees, a work pace essentially unheard of in the honeybee realm. Along this vein, it takes only 250 to 750 mason bees to do the pollination 60,000 to 120,000 honeybees could do. Six mason bees can pollinate a whole fruit tree in a single day!

How they Work

Mason bees emerge in late winter to early spring, which usually translates to mid-March in the Pacific Northwest. According to WSU Extension, if overwintered outdoors, they should emerge at about the same time the apple trees begin to bloom.

Mason bees lay their eggs in separate chambers along a tunnel, each encapsulated with mud. Because female mason bees are more important to the perpetuation of the species, the female egg is placed in the chamber farthest from the tunnel opening. This allows the 3-5 male bee eggs laid further forward to be sacrificed for weather, pests and predators. Plus, the male bees emerge first and wait to mate with the female (they only live two weeks), so it helps that they’re situated for easy exit from the egg tunnel.

Unlike honeybees, female orchard bees only live six to eight weeks after emerging. This is a small window for pollination, but overlaps with most fruit tree blooms in the early spring as well as a few berries and flowers. In the gardening world we generally associate mason bees with pollinating apple, pear, plum and cherry trees, but they also play a big role in pollinating early-blooming nut trees (almonds), some berries (blueberries, strawberries, blackberries), flowers (rhododendron, azalea, camellia), and many other native plants.

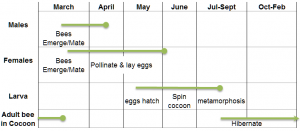

A Handy Guide to Mason Bee’s Life Cycle

(Courtesy of crownbees.com)

(Courtesy of crownbees.com)

Methods of Managing

Any protocol for mason bee care generally involves purchasing or constructing some sort of wooden structure drilled with 3/8” diameter holes. It is best to install this bee house on a south- or east-facing wall, shed or other structure that is generally warm and protected from intense wind and rain. Because mason bees travel between 100 and 200 yards in search of pollen, it isn’t all that important to have their nest situated close to your flowering plants.

The rustic method of mason bee management is a low-maintenance way to take advantage of the insects’ remarkable pollination power. Simply acquire one of the aforementioned wooden homes, affix it to a wall and either insert mason bees from the garden store or leave it for neighboring mason bees to find. At the end of the season, do nothing; leave the larvae to overwinter outside and emerge when they choose. The main drawback to this method has to do with hygiene. In two years or so the tunnels will become soiled or the bees will contract parasites and move to a new location, so it will be necessary to regularly install new boxes every growing season to keep them happy. Another option could be wooden, pre-drilled bee boxes that disassemble for easy cleaning (with a bleach solution), which have become available at garden centers more recently.

The straw method, on the other hand, requires a bit more energy but makes it easy to work with one nesting box year after year. In this approach, paper “straws” are slipped into the pre-drilled holes in early spring before store-bought bee pupae are inserted. Then at the end of the season (usually October to December) these straws can be removed and ripped open so that the cocoons may be inspected for disease, parasites and quantity. Then, the washing can commence. You can do this by either swirling the cocoons in sand for a few minutes and sifting off the grit with a sieve, or by stirring them in a mild bleach solution (1 gallon water: 1Tbsp bleach) for up to three minutes, then rinsing them in a container of fresh water and allowing them to dry completely before storing them in the refrigerator (36°F – 39°F). Air circulation is important, so check on your bees regularly for signs of too much or too little humidity. Finally, in March you can move them out to the bee box—stocked with fresh paper straws—and let the pollination begin!

The rent-a-hive method, a whole new approach is available to King County residents thanks to local mason bee maven Missy Anderson. Calling herself the “Queen Bee,” Missy rents hive kits of varying capacity for the season. Then at the end of the year, she will collect the homes for cleaning and selective culling and have them all ready to go again the following spring. So easy! Learn more at Missy’s website: www.rentmasonbees.com. Other beekeepers have offered their extra bees as well, sometimes for sale and sometimes for free due to an overabundance of pupae. Check the following resources for more information.

Resources for Bees and Supplies

Crown Bees – www.crownbees.com

Dave’s Bees – www.davesbees.com

Entomo-Logic – www.entomologic.com

Grow Organic – www.groworganic.com

Home Orchard Society – www.homeorchardsociety.org/masonbees

Knox Cellars – www.knoxcellarsmasonbees.com

Pollinator Paradise – www.pollinatorparadise.com

Raintree Nursery – www.raintreenursery.com

Rent Mason Bees – www.rentmasonbees.com

Ruhl Bee Supply – www.ruhlbeesupply.com

Seattle Farm Co-Op – www.seattlefarmcoop.com

Sky Nursery – www.skynursery.com

Swansons Nursery – www.swansonsnursery.com

Territorial Seed Company – www.territorialseed.com

West Seattle Nursery – www.westseattlenursery.com

Sources

Life Cycle of the Spring Mason Bee,

<http://www.crownbees.com/life-cycle-of-the-mason-bee>.

Moisset, Beatriz and Wojcik, Vicki. Pollinator of the Month: Blue Orchard Mason Bee,

<http://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/index.shtml>.

Orchard Mason Bees, WSU King County Extension, May 2010,

<http://county.wsu.edu/king/gardening/mg/factsheets/Fact%20Sheets/Orchard%20Mason%20Bees.pdf>.

Osmia Bees, Lewis County Beekeepers,

<http://lewiscountybeekeepers.org/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Osmia_Bees.357133840.pdf>.

Taylor, Lisa. Your Farm in the City.

For more information about flowering plants and how to keep all manner of pollinators a regular presence in your garden contact the Garden Hotline at 206-633-0224 or visit us on our website at www.gardenhotline.org. Learn more about attracting pollinators and other wildlife at Seattle Tilth’s “Planting for Wildlife” class in the fall http://seattletilth.nonprofitsoapbox.com/calendar/event/346.

Featured photo courtesy of Ray at https://www.flickr.com/photos/33rw/13176001585/.